Follow along at www.instagram.com/francisgilbert_bookclub if you like what you see.

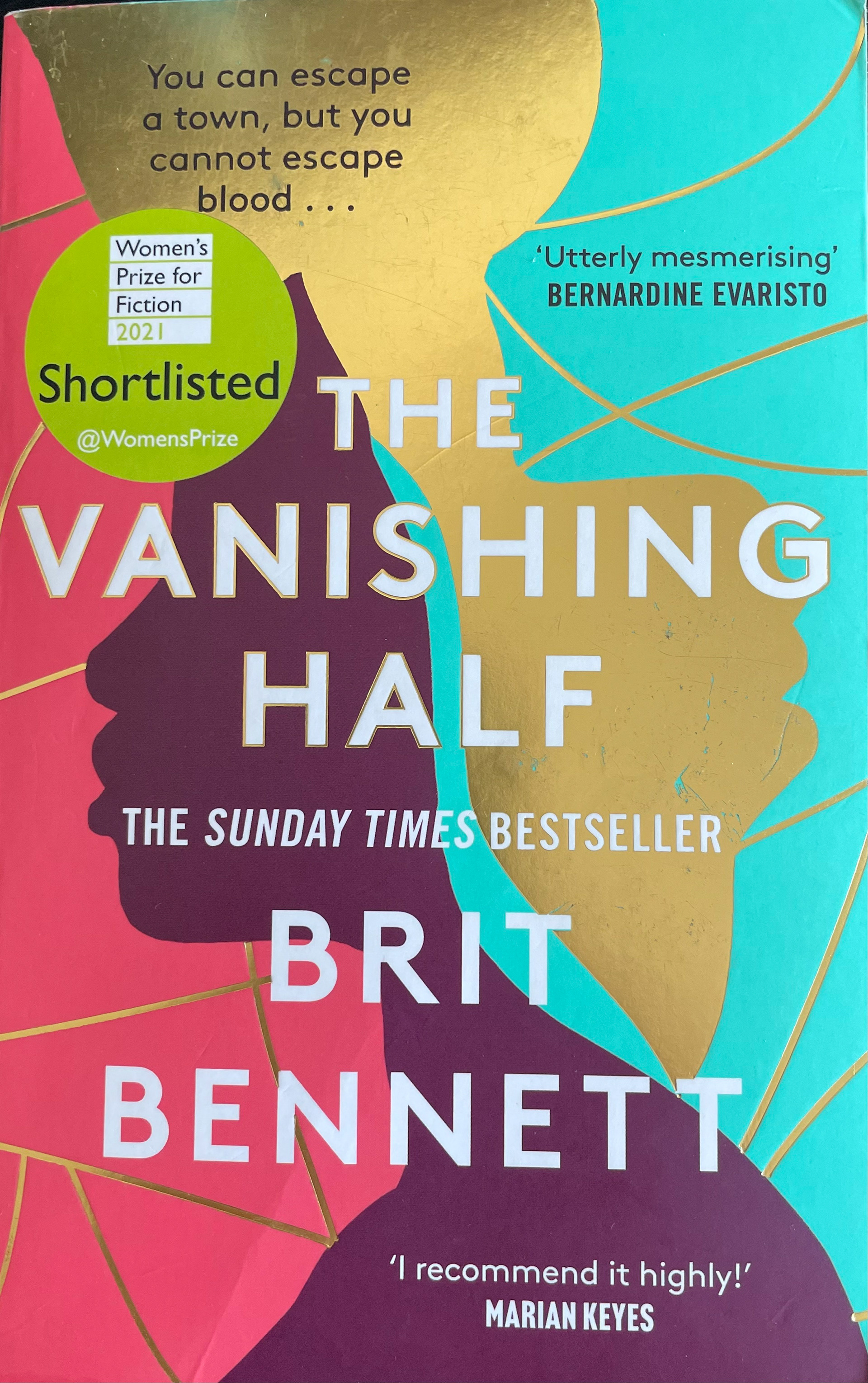

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

This gem of a novel is one you must seek to read if you haven't yet. I first heard of it back in 2020 during lockdown and whilst listening to podcasts galore. I knew it would be an eye-opening, well-written masterpiece and that it is. It is amazing. I don't like to use that word, but it truly is. Everything about Brit Bennett's The Vanishing Half fascinated and engaged me with its warm characters and insight into such charged issues of racial identity and family relationships.

The book is divided into Parts, set in 1968, 1978, 1982, 85, 86 and 88, which I love. It's modern yet gives references to troublesome historical pasts and enduring negative mindsets about community and how race is often considered to be an influencing factor. The novel thrums with pent-up emotion and the anonymity of the location of Mallard, the small town which has never been recorded in map form helps to give a haunting but sad fairytale element to the narrative.

Brit Bennett's description of true love and real relationships is wonderful. Characters like Jude and Reese, Desiree and Early, the twins' mother and her daughters Stella and Desiree, and even Jude and Kennedy show us relationships, or perhaps companionships, to aspire to, or learn from.

Absorbing stories, tales, anecdotes and experiences abound in this tightly woven network of messages to the reader.

I cannot wait to get my hands on The Mothers, Brit Bennett's first novel, which I am now eager to read, alongwith Nella Larsen's Passing, for which Brit Bennett has written the introduction and Girl, Woman, Other by Bernadine Evaristo, another novel I heard so much about during lockdown podcast time.

Here are further articles worth a read about this novel and its author Brit Bennett.

Anyone else read A Saint from Texas by Edmund White. Sisters who leave each other to explore different lives. Class is the dividing factor in this novel, but there are overlaps of a kind.

Finally, isn't my UK front cover beautiful!

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante

L'amica geniale. This novel is soul-destroying, but in a good way, if that is at all possible. The simplicity of Ferrante's narrative and the honesty behind her characters' observations about social class and status is so raw, it scrapes at the reader's own understanding of life and its levels of wealth. It is obvious to the foreign reader, reading in translation, that there is a deep admiration for position and reputation in Italian culture. Status is everything. Perbene. It is a sword hanging over girls from Italy and it dictates decisions and life choices.

There are numerous anecdotes and tales within this novel, which inflicted pity, but also fear for the women and girls living in the poverty of Italy. The description of two girls, drawn to each other, but destined for different layers of educated society was sad to read about. Lila is the friend , who aspires to much, borrowing four books a week, using her illiterate siblings' ID and keeping up with the study of her college-based friend, Elena. However, she ultimately aspires to a marriage into wealth and reputation for her family. It is sad, yet admirable, how much she is willing to give up.

The aggression and violence that is presented as mundane and normal for the community is sad. The feuding families reminded me of The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton in terms of the friendships and close loyalty that arises between many characters, as a result of the trauma and danger surrounding them in their normal home lives.

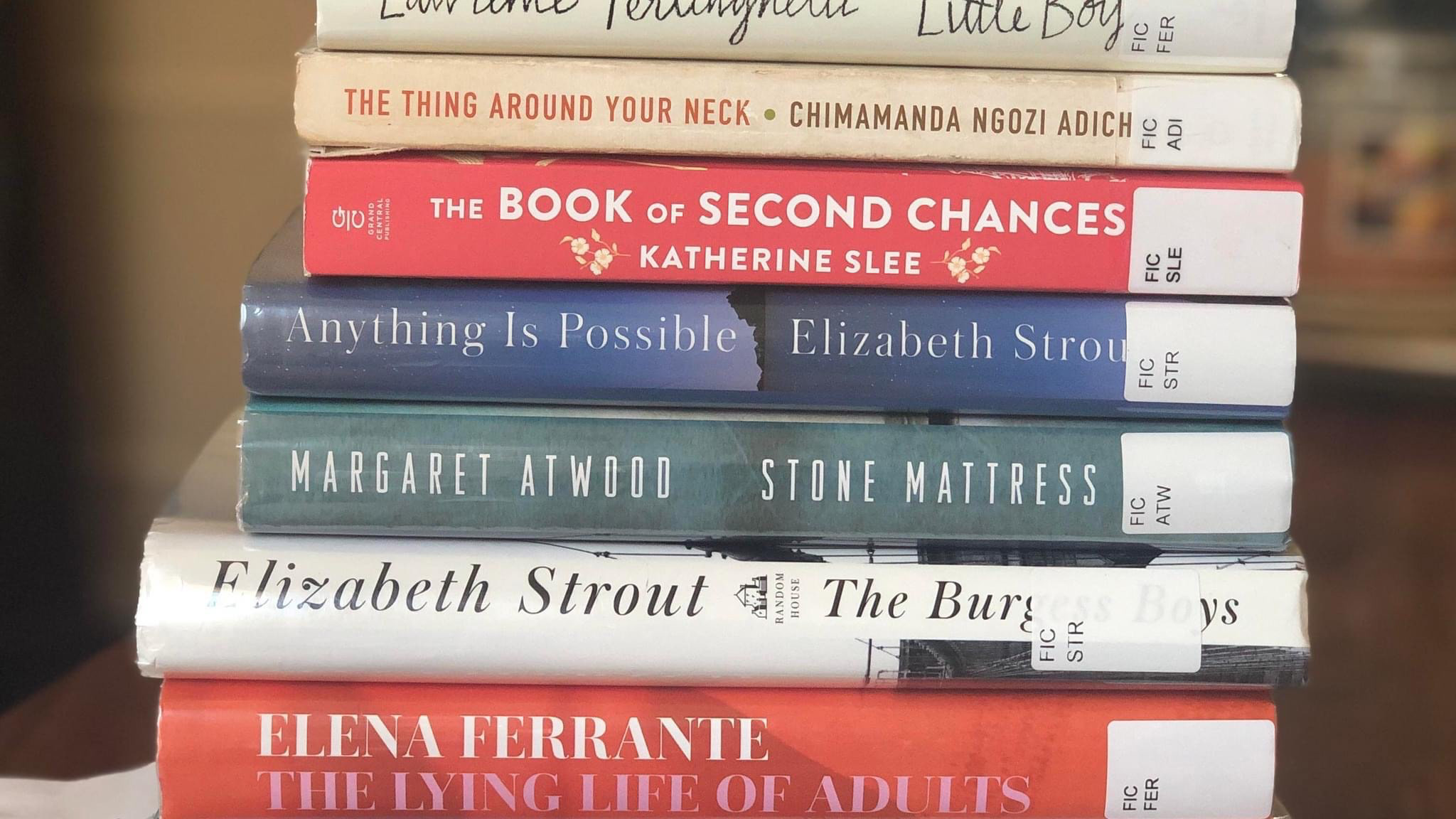

I enjoyed The Lying Life of Adults more than this novel, though I will be reading the others in Elena Ferrante's series. I have no access to the HBO TV series, but may seek it out, after I've finished reading the whole series.

Review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

Snow Country by Sebastian Faulks

Firstly, I hate to start with a negative, but I don't think the title was well-chosen for this novel. Perhaps I have missed a deeper meaning or symbolic connection, but unfortunately the title 'Snow Country' conveyed a completely different tale to the one I read, and I believe Faulks' narrative could have been more effectively anticipated with a more relevant title to match its content.

It was interesting to see Faulks' acknowledgement to the Japanese author Yasunari Kawabata whose 1935 novel Yukiguni was translated to Snow Country in 1956 by Edward Seidensticker. I'm not sure if there was any further relevance to this title choice.

Nevertheless, I did enjoy the structure of the novel, with three dated sections: 1914, 1927 and 1933. The central character of Anton Heideck is simpatico and strong enough to hold the plot together with his experiences and emotions. He comes across as a vulnerable man full of an endearing naivety, and I felt drawn to his journey, moving from an innocence towards experience of life and love, gained from living through World War I and its aftermath.

This novel is the second in Faulks' planned Austrian trilogy, the first novel being 'Human Traces', published in 2005. The location of this first novel, which is the sanatorium Schloss Seeblick is where the novel continues along with initial story setting and establishment of relationships in Vienna.

Love is a central theme holding the plot together, covering doomed love in pre-war Vienna, the frailty of mentally afflicted loved ones and psychoanalytical theories about sex, love and human relationships.

Faulks' main narrator is a journalist and this works well since it allows him to include historical context and backstory alongside the action and dialogue of the characters.

Although I continue to consider the novel 'Birdsong' to be spectacular literature, and its veracity in presenting historical events and emotions masterful, I'm afraid his other novels, including this one, have not matched up to his literary reputation.

When Sebastian Faulks finishes the third novel in this Austrian trilogy, I will read all three novels in sequence and am sure I will gain much from Faulks' knowledge and insight of European history.

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

The Paper Lovers by Gerard Woodward

For me, the ending of this novel was not satisfactory. I was expecting a completely different end-point and had thought I was collecting clues from the narrator's opinions, dialogue and movements in the plot. However, I got it wrong! Having said that, the message or underlying controversial comments included in the novel by Gerard Woodward have lingered with me and for that, I do have some appreciation for this novel.

I love the front cover and the title was appealing for me. I saw how the concept of paper and how it is made through the destruction of something else was used expertly by Woodward to weave his themes together: adultery, redemption, truth, honesty and deceit. I greatly enjoyed learning details about the way recycled paper is made, ironically through breaking and tearing of the original valued product. The references to the wonderful artisan paper shop and the publishing agency run by the husband and wife team was also interested for me.

In the current book publishing world, I believe this novel would be labelled as 'quiet', since the majority of the text is internal choices and decisions made by characters, with very little dynamic action. I liked the plot structure where the second half was without chapters, giving us the wife's perspective. I have to admit, I did not manage to connect with the protagonist, the male Arnold in the opening chapters and throughout his narration, he seemed a wholly unlikeable character.

The Martin Guerre character made me think of the voyeuristic, unstable character in 'Enduring Love' by Ian Ian McEwan. These anomalous aspects of the novel intrigued me and having finished, without feeling a love for the book, I know there is so much to prompt discussion within this novel; religion, parenting, gender roles, trust and honesty, modern relationships, publishing and editing industries, and so much more.

My secondary school teacher background would make me argue this novel could be taught and used in the classroom as a controversial prompt for debates.

To give a final brief overview of the story of this novel, it starts with a family scenario, using a sewing machine as a central motif. The sewing machine is a gift for the couple's daughter, which turns out to be too old for her and thus becomes her mother's tool, allowing her to invite other mothers from her daughter's school to her house for sewing evenings.

The father, Arnold is a poet and the couple's publishing company linked with the mother's paper shop has published his one collection of poems. This company comes under attack by a young student poet, who is determined to be published by the company, so causes a disturbance to the mother and shop-owner Polly.

There is a twist in the tale, causing the reader to be voyeuristic of something unnerving, which develops and encompasses the family, poisoning the foundations of the family at its roots. From here, the story twists and turns, in a 'quiet' fashion and the reader is gradually unsettled and left feeling a little empty.

A devastating story, but rather spiritual, making us wonder if redemption is ever possible, whether new can be made from old and ultimately if creativity needs more sensitive handling due to its propensity for self-destruction.

Review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

The way in which Elizabeth Strout has steadily built up her representations of American life, and interwoven lives of recognisably real characters in her novels (Anything is Possible, My Name is Lucy Barton, Lucy by the Sea and even Olive Ketteridge and Olive, Again) is awe-inspiring.

I've noticed comments from readers who found this novel not to be as great as her Olive Ketteridge, winner of the Pulitzer prize in 2009, though that has made me wonder if it was Strout's intention to release small anecdotes, soundbites, cautious revealing of emotions, and photographic screen shot descriptions of her vulnerable characters' lives, with an undramatic simple narrative? That's what life is like, isn't it? Nothing works in chronological order. The architecture of lives and family sagas are built upon and developed piece by piece. This style works for me.

In this narrative, as in My Name is Lucy Barton, Lucy's voice follows a stream of consciousness and rather conversational style of telling the reader of her continued coming-of-age. She comes across as a young girl, still trying to find herself and understand who she has been and who she has become. She is a vulnerable character, in terms of her past experiences, which are hinted at in this novel too. However far she has travelled from her troubled roots and however strong she appears to those in her adult world, we are still pushed to feel enduring pity for her. Her honest outpourings regarding her feelings for her ex-husband William, her daughters and people she has been introduced to by her mother-in-law Catherine keep coming back to haunt her, such as the way her mother-in-law introduces her as, '...Lucy. Lucy comes from nothing.'

Strout manages to prompt readers to visualise Lucy as a young and vulnerable girl, yet we need to keep reminding ourselves that she is in fact an older mother with two grown up daughters. Her narrative is one of innocence and matches the message of the novel, in that it is hard to escape your past and there are 'quiet forces that hold us together.'

Interesting to hear whether there is an order in which to read Strout's novels. I would argue that there is not, and that each novel ties together loose threads of a community, and of characters who contribute to the nature of a place. In reading one of Strout's novels, it is hard not to feel compelled to seek out more and read another, if not all of her novels, which are all interconnected through characters' relationships and experiences.

I continue to be a huge fan of Elizabeth Strout. This novel made me sad and pitiful in some ways towards the central character of Lucy Barton, yet the way in which Strout allows her characters to quietly speak to readers and tell their stories as they choose is beautiful and shows kindness for her characters and their troubles, as if they truly are real people we know and love. Every time I finish a novel by Elizabeth Strout, I feel as if I'm addicted to her style and need to find more of her writings to read. I have My Name is Lucy Barton and Lucy by the Sea, Abide with Me and Winter, as unread novels!

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus

First of all, let me say how much I love the front cover of this novel with its subtle image components like the laboratory reflections in the glasses, the yellow 2B pencil and simple feminine facial features. The cover gives the impression this is a commercial book aiming to catch the reader's attention. It does do that with its contrasting orange and cobalt blue text. It fits with one of the cringe-worthy soundbites of the novel argued by the male producer character, Walter Pine, that: 'sexy was in, science was out.'

However, the book is a clever construction of literary conflict! Interesting that opinions at a Book Club of mine, for which I read this beautiful hardback, were of the wish to classify this book as a literary, rather than commercial novel. Let me explain some of our reasoning!

The novel moves, sometimes quickly, between points of view in an experimental manner, which is often frowned upon in modern novels, yet here it seems fit for purpose. Needless to say, some may disagree when they realise that a central voice and perspective in the plot is that of the dog, named Six-Thirty by the main protagonist Elizabeth Zott.

The unique combination of scientific information (not a lot, but that's okay if we consider this as a starting novel in this new genre) intermingled with story and human narrative that you would expect in a romance novel allows the reader to empathise with women of the 1950s era. We're also urged to laugh at how under-rated women have been in the past and perhaps still are. The New York Times Book Review rightly points out that, 'Feminism is the catalyst that makes Lessons in Chemistry fizz like hydrochloric acid on limestone.'

The second half of the novel had the most impact for me and I was gripped from about Chapter 23. I particularly loved the repeated trope at the end of many chapters in the second half when Elizabeth Zott speaks out to the children of her audience. So clever. The ending of each chapter from this point onwards had a powerful and humorous message and meant we were cheering along for our central female heroine to succeed in her uphill journey to proving her point. Her point being that women can do everything that men can and should not be held back.

Elizabeth Zott's daughter, supremely named Mad represents the future and along with Harriet, their neighbour, their rescued stray dog Six-Thirty, a fellow parent and colleague Walter Pine, the way these characters support and collaborate to make changes in their world is forward thinking and a pleasure to read. This was a most enjoyable read.

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt

Lovable, witty characters with intriguing and authentic personas fill this novel to the brim with a warmth that overflows. This is a truly heart-warming story with a beautifully orchestrated plot which weaves together characters’ lives. Some of the connections in places are obvious, yet the dramatic irony makes seeking the clues alongside the characters rewarding. One of the main narrators is an unusual one offering an alternative perspective to our common human way of thinking. I learnt a great deal about the sea, grief, perseverance, friendship, and cephalopods!

The dialogue composed by debut author Shelby Van Pelt is exact for the way I imagine her characters to converse and interact. It presents the underlying kindness of all her characters in such an effective way I found myself reading up about her as I reached the half-way point of the novel. I wanted to know more about Van Pelt, her choice to write about Swedish culture, and her reasoning for focusing on an aquarium in Seattle as her main location. I love her author’s backstory.

This is one of those books you will want to recommend to everyone: your siblings, your parents, your friends, your colleagues, your grandparents and even your older children. It is a tale with underlying messages, whether intended or not, which I feel has enough depth to provide starting points for conversations amongst people of all generations. The primary themes include grief and friendship: they are presented to the reader in an honest and simple manner using narrative tools, which push the reader’s internal mind-set towards empathy of the strongest kind.

I was reminded of the beautiful octopus featured in the animated short film adaptation of Oliver Jeffers’ picture book Lost and Found. In this favourite book of mine, the small boy and his boat are rescued by the octopus after a storm, which had threatened to scupper the boy’s journey back to his friend, a penguin from the South Pole.

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert