The Best Short Stories 2022 [The O. Henry Prize Winners] Edited by Valeria Luiselli

I always find the short story genre a hit-or-miss reading experience. I understand that the structure of such short fiction needs to be tight, resonant in terms of its message to the reader and usually a single plot, yet I find the inconclusive nature of much short storytelling to be frustrating. I like a neat, tidy ending, whether it be a happy or tragic one. I often find the resolutions of prize-winning short stories to be unsatisfactory, perhaps highlighting an amateur writer way of thinking.

Many of the stories in this collection do not end with a definite conclusion. For me, they leave too many unanswered questions, which affects whether I'm left with a lasting message, and for many of these stories, I was not.

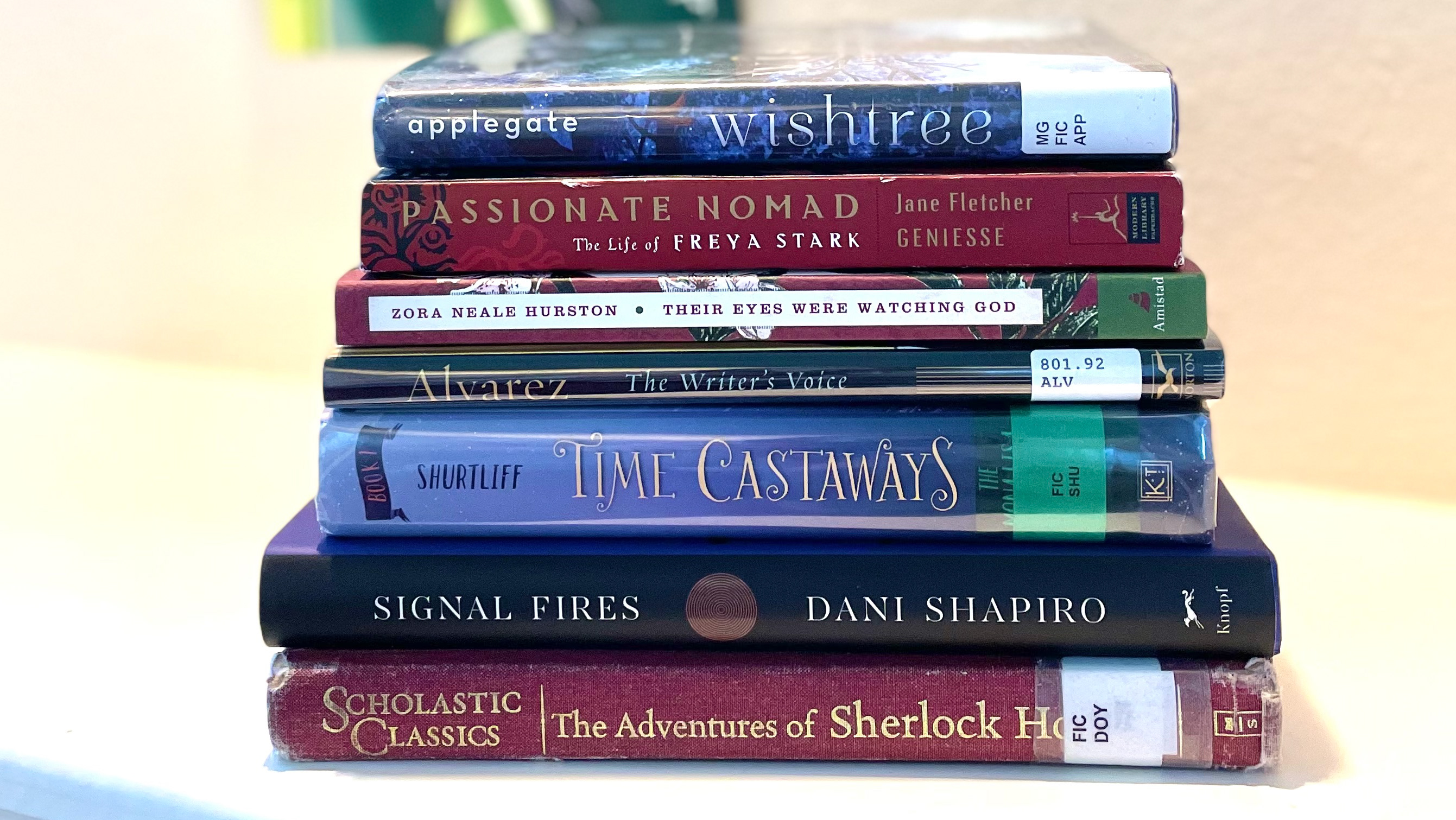

Ten of the twenty stories in this collection are in translation. Of these, translated from Spanish, Polish, Bengali, Norwegian, Greek, Russian and Hebrew, my favourite is that of Samanta Schweblin called An Unlucky Man. I enjoyed reading the author's explanation of its personal and political nature and her aim to show that 'without the reader's fears and prejudices, this story wouldn't work.' It reminded me of a scene from Dani Shapiro's latest novel Signal Fires.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's story Zikora and 'Pemi Aguda's story Breastmilk stand out from the crowd. Interesting since they address the same topics of motherhood and childbirth. The imagery and 'grittier and more realistic' description of birthing a child presented beautifully in both of these stories appealed to me.

A number of the stories deal with the Covid-era. They are current and engaging with fresh representation of what will become interesting historical documentation of this century. A collection of stories all more closely tied to the central pivot of the pandemic might have worked more strongly than having them dotted amongst other stories with no mention of Covid-19.

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

Lessons by Ian McEwan

"Well, there's a pretend book I want to read. It's very interesting and so enormous that I don't think I'll ever get to read it all."/"Who's in it?"/"Absolutely everybody, including you. And it's a hundred years long." Ian McEwan

Ian McEwan's latest novel is long. In fact, the way McEwan's protagonist Roland Baines responds to his granddaughter's question about what he is reading sums up the author's intention with this novel. It appears he wanted to document in literature the downward spiral of events which have led us to today's 21st century state of affairs. The plot spans incidents, both personal and public from the Baines' childhood in Libya in the 1950s, his fatherhood in the 1980s through to the current pandemic era.

McEwan's character lives in London, is left by his German wife Alissa at the outset, leaving him with their 7 month old son. She says "I've been living the wrong life." She takes an independent leap away from parenthood to enable her creative calling to immerse her. Since our head is with the male protagonist who is left behind, himself troubled by past incidents, it is an uncomfortable spider's web of life experiences and decisions which pulls us through the novel. This is especially true since the parallel opening image is his memory of being seduced by his piano teacher when only 14, "This was insomniac memory, not a dream. It was the piano lesson again..." He is a passive observer of life, which does not do him any favours.

"One great inconvenience, according to Roland, lay in being removed from the story. Having followed it this far he needed to know how things would turn out."

I do enjoy McEwan's satire and subtle wit. There's not a great amount in this novel, but it is there. The female characters are the ones who dole out the 'lessons' the reader should learn or not! Though, later in the book, Baines' connection with his grand daughter is perfect and "He saw her point. A shame to ruin a good tale by turning it into a lesson."

Here are further selected quotations I have found best present the epic content you will find in Ian McEwan's apt narrative.

"He held more in memory and reflection than he could have found in his journals. There were currents, plot lines, developments that no one could have predicted but in those vanished pages he had not even posed the questions. By what logic or motivation or helpless surrender did we all, hour by hour, transport ourselves within a generation from the thrill of optimism at Berlin's falling Wall to the storming of the American Capitol? He had thought 1989 was a portal, a wide opening to the future, with everyone streaming through. It was merely a peak. So many lessons unlearned."

"Roland's bad dream was of freedom of expression, a shrinking privilege, vanishing for a thousand years."

"...It was a mistake to have mentioned his imaginary history of the twenty-first century. It was not a children's book...Yes, a mistake to mention such a book when he was passing on to her a damaged world."

"Come on Grandpapa. It's this way. Frowning with concern, she took his free hand in hers and began to lead him across the room."

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

The London Eye Mystery by Siobhan Dowd

This is a great read-aloud bedtime story book for upper primary school children. My children have never lived in the UK or London, only visiting family during the summer, but this novel uses places in London such as the Underground and the London Eye for its setting. My children are gripped by the mystery and love the description of place.

We shall see how the mystery is solved as we still have a few more chapters to go. Must mention briefly that the middle chapters are a little repetitive and not all needed.

The narrator is young Ted and he has some unique perspective and tendencies to explain and define all that he sees, which makes the story accessible to my 9 year old (and 6 year olds!).

I ought to also admit I skipped over a few references to sex and crime, which I thought were unnecessary and not appropriate for my readers.

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng

This is a chilling story that draws our attention to the 'blurry overlaps between resisting, tolerating and colluding' in the face of authoritarian political choices that are out of our hands.

A twelve-year-old boy Noah Gardner, called Bird by his mother, is the character we follow who tells us of his current living arrangements with his father, but no longer with his mother. His father has lost his job as a linguistic professor, thus they live in university accommodation. They do not speak of the third missing member of their family. We learn quickly that Bird's father seeks to conceal and quieten their existence and Bird is encouraged not to ask questions, not to stand out too much or stray too far from their 'safe' home.

The dystopian element of the novel is harrowing and cautionary since the tale is set in a very close future, with slight shifts in the status quo of a recognisable 21st century. The laws including PACT (Preservation of American Culture and Traditions) and hounding of PAO (Persons of Asian Origin) following an economic Crisis govern the lives of Bird and his father.

Bird's mother, Margaret is a Chinese American poet whose poem and its line 'Our missing hearts' was used by an activist, out of context, to heighten awareness of the horror of children being torn from their families and this consequently placed her in danger for her words. She made the decision to leave her family when Bird was nine attempting to avoid bringing risk to her husband and son.

Celeste Ng uses libraries and books as the central elements of Bird's journey to find his mother after receiving a message she has left behind. The protective nature of libraries and librarians is comforting as their existence is entwined into both Bird and his mother's narrative. Protective, nurturing, informative, communicative institutions holding on in a form of muted resistance.

The central narrative of the story includes Margaret's retelling to her son of events leading up to her disappearance. There is mention of artistic guerilla incidents including red yarn-covered trees and use of Margaret's poetic words 'All our missing hearts' to transmit messages. These scenes are described beautifully and spell out the power of peaceful protest. Yet, they horrify us too in showing the dystopian world where it is necessary to fight at dismantling long-established systems.

Celeste Ng's writing style is mesmerising. Her calm confidence of narration is clever with its layers of underlying significance. There are powerful cultural references I know I have not understood fully, including the references to cats from the Japanese fairy tale. As a result, this is a novel you can read for its comments on emotional family bonds as well as for its representation of a 'prototypical quest story that has the benefit of maybe being real . Or if it isn't it accords with history.'

There is so much more in this novel I haven't been able to mention in this review. I recommend this book as a compelling, necessary but also challenging read.

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert

Mrs Poe by Lynn Cullen

This is not a biography and consequently I enjoyed it as a piece of fiction, but struggled with the melding together of real history and persons and wholly imagined incidents of the plot. Set in 1845 in New York City, the description and imagined setting of this time period was most interesting and details did bring the history of the expansion of the city at this time alive.

Informing of historical figures and literary creative celebrities of the past from storytelling is a valuable tool which authors use in the historical fiction genre, yet in this novel, much felt dangerously unsubstantiated. It is creative license, of course, so no need to complain really, especially since so much else has been written, under the guise of non-fiction about poor Edgar Allan Poe. His reputation has been soiled repetitively in literature, not least by Griswold who appears in this novel.

However, in this novel, it felt like a missed opportunity for reinforcing Poe's character as mysterious, worthy and beatific, and above needing to explain himself against critical reviews. Instead, the character of Poe is shown to be cajoled by women, foolish in his decision-making and untrue to his own literary prowess. There's no mention of his alcohol addiction, or possible opium use, which surprised me!

Perhaps that is in fact what ailed Poe? If that is the case, Lynn Cullen has done a great job in showing Poe to be troubled and without true supporters or family to guide his career and passage through life.

Although the central voice and protagonist of the historical novel, Frances Osgood is not one to whom I found easy empathy. Her position as an aspiring poet is diminished by her obsession and love for Edgar Allan Poe, meaning she loses her inspiration and creativity. She is unable to appreciate the value of her husband's return (albeit after adultery and ill-treatment) and the way he understands her as a person. I didn't like the husband character, yet he was a father and promoter of his wife's creative spirit, unlike Poe who seemed to want to drain her.

Was entertained by the novel and will have fun discussing with my Book Club. Also now intrigued to read more of Edgar Allan Poe and the controversies surrounding his penmanship and brief life.

review by Christina Francis-Gilbert